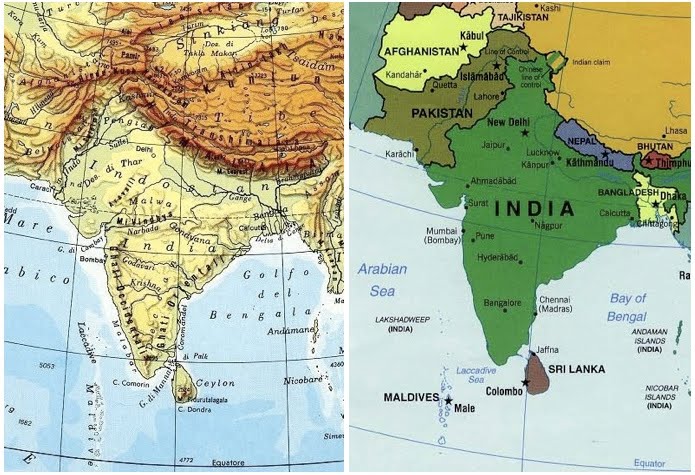

An

Indian Ocean archipelago of more than 1,992 coral islands scattered

across the Equator, the Maldives is known for its emerald green waters

and pristine beaches. Visiting tourists usually view it as a tranquil

paradise. Maldivian politics, though, have rarely been peaceful.

A British protectorate until 1965, the Maldives has been under authoritarian rule for most of its post-Independence years. Maumoon Gayoom ruled with an iron first for 30 years. Yet he was not immune from challenges. In 2003, mass protests erupted over torture in prisons. These quickly snowballed into a powerful movement for democracy, forcing Gayoom to introduce political reforms. Those reforms in turn culminated in a new Constitution, legalization of political parties and multi-party elections to the presidency, parliament and local councils.

Gayoom’s authoritarian rule ultimately ended in 2008, although his influence remained strong. Mohamed Nasheed of the Maldivian Democratic Party (MDP) defeated Gayoom to become the country’s first democratically elected president.

Nasheed and the MDP faced enormous difficulties. With Gayoom-era appointees and cronies firmly entrenched in the judiciary, bureaucracy, police and military, the Maldives’ nascent democracy was stymied. Meanwhile, anti-democratic forces joined hands with religious conservatives and accused Nasheed of working with Jews and Christians and undermining Islam. Almost from his first day, Nasheed was at loggerheads with the judiciary. Officials in various state institutions ignored the Executive in making decisions, undermining Nasheed’s authority. Massive demonstrations against the president and the MDP were organized, plunging the archipelago in unrest and instability.

Then, on February 7 last year, Nasheed stepped down. Was it voluntary or was he pushed? In a New York Times op-ed, the former president claims the later, writing of police officers and army personnel loyal to the previous regime mutinying and forcing him “at gunpoint, to resign.” He continued, “I believe this to be a coup d'etat and suspect that my vice president, who has since been sworn into office, helped to plan it.” This account is denied by the vice president – now president – Mohammed Waheed, who claims that Nasheed “resigned voluntarily.” Dismissing coup allegations, Waheed says that he became president through “a constitutional transfer of power,” after Nasheed resigned.

Eighteen months on, Maldivians continue to heatedly debate the events of February 7. Early last month, they finally got the chance to have their say in a presidential election. The result was emphatic, yet not decisive: Nasheed won 45.5% of the vote. His opponents – Abdulla Yameen of the Progressive Party of Maldives (PPM) (25.35%), the Jumhooree Party’s Gasim Ibrahim (24.07%) and the incumbent Waheed (running as an independent) (5%) – were left trailing far behind. The outcome? A run-off.

Scheduled to take place on September 28, the run-off vote was to be a clash between Nasheed and Yameen. The latter is Gayoom’s half-brother.

A British protectorate until 1965, the Maldives has been under authoritarian rule for most of its post-Independence years. Maumoon Gayoom ruled with an iron first for 30 years. Yet he was not immune from challenges. In 2003, mass protests erupted over torture in prisons. These quickly snowballed into a powerful movement for democracy, forcing Gayoom to introduce political reforms. Those reforms in turn culminated in a new Constitution, legalization of political parties and multi-party elections to the presidency, parliament and local councils.

Gayoom’s authoritarian rule ultimately ended in 2008, although his influence remained strong. Mohamed Nasheed of the Maldivian Democratic Party (MDP) defeated Gayoom to become the country’s first democratically elected president.

Nasheed and the MDP faced enormous difficulties. With Gayoom-era appointees and cronies firmly entrenched in the judiciary, bureaucracy, police and military, the Maldives’ nascent democracy was stymied. Meanwhile, anti-democratic forces joined hands with religious conservatives and accused Nasheed of working with Jews and Christians and undermining Islam. Almost from his first day, Nasheed was at loggerheads with the judiciary. Officials in various state institutions ignored the Executive in making decisions, undermining Nasheed’s authority. Massive demonstrations against the president and the MDP were organized, plunging the archipelago in unrest and instability.

Then, on February 7 last year, Nasheed stepped down. Was it voluntary or was he pushed? In a New York Times op-ed, the former president claims the later, writing of police officers and army personnel loyal to the previous regime mutinying and forcing him “at gunpoint, to resign.” He continued, “I believe this to be a coup d'etat and suspect that my vice president, who has since been sworn into office, helped to plan it.” This account is denied by the vice president – now president – Mohammed Waheed, who claims that Nasheed “resigned voluntarily.” Dismissing coup allegations, Waheed says that he became president through “a constitutional transfer of power,” after Nasheed resigned.

Eighteen months on, Maldivians continue to heatedly debate the events of February 7. Early last month, they finally got the chance to have their say in a presidential election. The result was emphatic, yet not decisive: Nasheed won 45.5% of the vote. His opponents – Abdulla Yameen of the Progressive Party of Maldives (PPM) (25.35%), the Jumhooree Party’s Gasim Ibrahim (24.07%) and the incumbent Waheed (running as an independent) (5%) – were left trailing far behind. The outcome? A run-off.

Scheduled to take place on September 28, the run-off vote was to be a clash between Nasheed and Yameen. The latter is Gayoom’s half-brother.

http://minivannews.com/politics/six-protesters-released-on-condition-that-they-dont-participate-in-protests-for-two-months-67140

RispondiEliminahttp://www.globalist.it/Detail_News_Display?ID=49504&typeb=0&Mutande-appese-al-tribunale-alle-Maldive-si-protesta-per-le-elezioni

RispondiElimina