It’s a pristine white circle, so large it stands out like a sore thumb on Google Earth.

Surrounding the 80,000 seat arena, regarded as the jewel in the crown of London’s Olympic village, is a controversial £7m fabric wrap provided by one of the world’s largest chemical manufacturers, Dow Chemicals.

The wrap came after Dow signed a lucrative deal in 2010 to become one of the 11 Worldwide Olympic Partners.

While the wrap itself, a series of triangular white panels, looks plain and inoffensive, the chemical giant has a somewhat darker legacy.

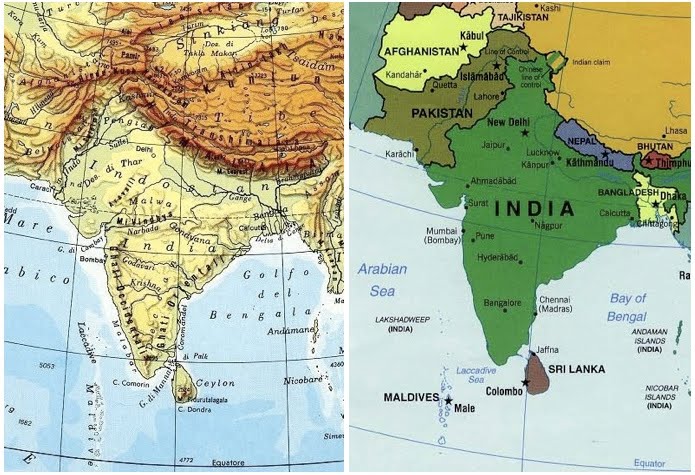

Almost 30 years ago, in December 1984, the Indian city of Bhopal was the scene of one of the biggest industrial disasters in history, when a toxic gas leak at the Union Carbide pesticide plant.

The leak killed between 7,000 and 10,000 men, women and children in the immediate aftermath. Another 15,000 or so died in the following years. More than 100,000 are estimated to continue to suffer from serious health problems as a result of the leak. .

Since 2001, Dow has been 100% owner of Union Carbide Corporation (UCC), the company whose Indian subsidiary owned and operated the Bhopal plant responsible for the 1984 gas leak disaster. Union Carbide walked away from Bhopal without cleaning up, without disclosing the exact nature of the gas that leaked from its plant, and without paying adequate compensation to the victims. Despite this, UCC and its owner, Dow, deny any responsibility for the ongoing tragedy of Bhopal.

Beaten by police

Away from the fanfare of the London games however, there has been no thorough investigation into why the Bhopal leak happened and into the impact it has had on people’s lives. Survivors have not been given the medical care they need, nor fair compensation.

It is perhaps not surprising that Bhopal activists fighting for justice and a clean future are still so angry.

“Young children are forced to give up school and work because their parents have been affected by the gas,” Safreen, a student activist told Amnesty International when the organization visited Bhopal recently.

“Others are born with deformities and illnesses. I want children in Bhopal to breathe fresh and clean air, drink clean water and stay healthy,” she said.

“I dream that Bhopal will be a better place to live and that the companies will take responsibility for causing so much suffering.”

Safreen is only 17 and wasn’t born when the disaster happened. She has joined a children’s group fighting for survivor’s rights and dreams and hopes to train as a doctor to help people cope with the health problems that still linger here.

Many Bhopalis are old enough to remember the night of the gas leak and are still living with the consequences.

“My whole life changed after the gas leak,” activist Hazra Bi told Amnesty International.

“My husband’s health was so severely affected by the gas that he died. Raising four children on my own was traumatic, “she said,

Hazra

Bi’s children and grandchildren were born with medical problems she

thinks were caused by the gas leak. The official compensation her family

received was too little, too late.

“It’s been round the clock physical and mental agony for almost three decades. But I won’t give up the fight. It’s a question of Bhopal’s future generations,” said Hazra Bi.

50-year old Shahazadi Bi is a resident of Bhopal’s Blue Moon Colony, a housing society situated next to a pond still contaminated with toxic waste.

“Soon after the gas leak my periods became very irregular. At times I would bleed three times in a month and then nothing for two or three months. My daughters also suffer from this problem, as did many women in Bhopal after the gas leak,” she told Amnesty International.

A dusty ride across town took the Amnesty delegation to the house of 85-year-old Rampyari Bai, who has taken part in every single march organized by survivors in Bhopal.

She brandished a bruised ankle and described how police beat her up during the anniversary rally in December last year. Sitting in her small dark flat lit by a neon lamp even in the middle of the day, it was clear her fighting spirit is still intact. In a strong firm voice, she explained how difficult it had been to get even meagre compensation and basic health care.

“It’s high time Dow took responsibility for almost 30 years of suffering,” she said.

“The compensation I received is a mockery. But I will fight for our rights and justice until my last breath so another Bhopal doesn’t take place in the world. I want the next generation to have happy lives.”

Back in London, the Dow’-sponsored plastic panels are swaying gently in the wind while organizers scuttle round preparing for the opening ceremony next week.

Amnesty International is calling on the London Organising Committee for the 2012 Olympic Games (LOCOG) to retract its statement denying a connection between Dow Chemicals and the Bhopal catastrophe.

“Bhopal is an ongoing disaster and one of the worst abuses of human rights by a corporation in the last 50 years,” said Madhu Malhotra , Director of Amnesty International’s Gender programme.

“Given the toxic legacy attached to Dow Chemicals, it seems absurd that LOCOG chose this company to sponsor an event billed as the most sustainable Games ever. It’s time they admit their mistake and apologize.”

“It’s been round the clock physical and mental agony for almost three decades. But I won’t give up the fight. It’s a question of Bhopal’s future generations,” said Hazra Bi.

50-year old Shahazadi Bi is a resident of Bhopal’s Blue Moon Colony, a housing society situated next to a pond still contaminated with toxic waste.

“Soon after the gas leak my periods became very irregular. At times I would bleed three times in a month and then nothing for two or three months. My daughters also suffer from this problem, as did many women in Bhopal after the gas leak,” she told Amnesty International.

A dusty ride across town took the Amnesty delegation to the house of 85-year-old Rampyari Bai, who has taken part in every single march organized by survivors in Bhopal.

She brandished a bruised ankle and described how police beat her up during the anniversary rally in December last year. Sitting in her small dark flat lit by a neon lamp even in the middle of the day, it was clear her fighting spirit is still intact. In a strong firm voice, she explained how difficult it had been to get even meagre compensation and basic health care.

“It’s high time Dow took responsibility for almost 30 years of suffering,” she said.

“The compensation I received is a mockery. But I will fight for our rights and justice until my last breath so another Bhopal doesn’t take place in the world. I want the next generation to have happy lives.”

Back in London, the Dow’-sponsored plastic panels are swaying gently in the wind while organizers scuttle round preparing for the opening ceremony next week.

Amnesty International is calling on the London Organising Committee for the 2012 Olympic Games (LOCOG) to retract its statement denying a connection between Dow Chemicals and the Bhopal catastrophe.

“Bhopal is an ongoing disaster and one of the worst abuses of human rights by a corporation in the last 50 years,” said Madhu Malhotra , Director of Amnesty International’s Gender programme.

“Given the toxic legacy attached to Dow Chemicals, it seems absurd that LOCOG chose this company to sponsor an event billed as the most sustainable Games ever. It’s time they admit their mistake and apologize.”

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento