The constituent assembly elections held on 19 November

and the general strike call issued on 12 November have created a climate

of social tension that has directly affected the news media. Caught

between election supporters and opponents, the media have been the

victims of violence.

“The incidents involving the

media testify to how little freedom of information the authorities have

allowed, especially during the elections,” Reporters Without Borders

said. “Many opposition newspaper have expressed fear about covering

events in such an environment.

“This fear is shared

by the newspaper distributors, who have been the target of intimidation.

We call on both the government and the opposition to try to defuse the

tension in order to allow the media to operate without fear for their

safety.”

Reporters Without Borders added: “The

deployment of large numbers of police must not be used as a pretext for

targeting newspapers that want to cover the election boycott. On the

contrary, the police must guarantee the safety of news providers.”

Radio Dolpa journalist Subarna Kumar Dangi

was badly injured in an attack by six members of the Young Communist

League (YCL) as he was returning to his home in Dolpa on 8 November. He

told the RSS agency that one of his assailants had said: “He’s the one who wrote the articles about us. Let’s break his hand.”

The

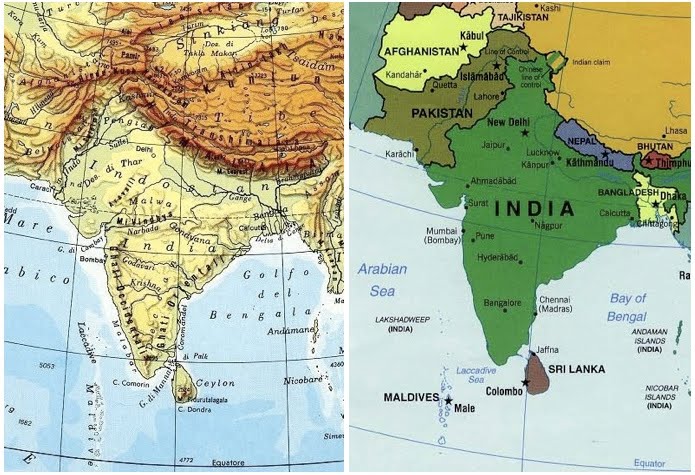

YCL is youth wing of the Unified Communist Party of Nepal-Maoist

(UCPN-M), which is one of Nepal’s leading parties and which has

participated in recent coalition governments.

Gopal Dewwan, the editor of the weekly Bishwastasutra and a correspondent for he daily Blast Times,

was the target of a shooting attack by unidentified individuals while

at his office in Chatarline on 10 November but managed to avoid being

hit. The police said they were trying to identify the attackers and

their motive.

Ramesh Rawal, the editor of the monthly Jana Swayamsevak,

was arrested by plainclothes police on 14 November in Singha Durbar,

and was held for four hours in a police station. At the same time, Dipendra Rokaya, a journalist with pro-Maoist Radio Mirmire, was the target of an abortive arrest attempt at his radio station.

Most of these acts of violence were attempts to gag news providers. This was particularly clear in two incidents. In one, RSS reporter Raju Bishwokama

was manhandled by border police on 7 November when he photographed them

paying money for illegally imported goods. His camera was seized and

the photos were deleted.

In another incident, Nagarik Daily reporter Dhruba Dangal’s camera was seized on 20 October after he took photos of police responsible for election security and his photos were deleted.

The

newspapers were also targeted during the strike, which was called by 33

parties led by the Communist Party of Nepal-Maoist (CPN-M), a splinter

group from the UCPN-M.

On the first day of the

strike, 12 November, newspaper distribution was badly affected

throughout the country, especially after stones were thrown at the truck

carrying the Nagarik and Republica daily newspaper near Gwarko, south of Kathmandu.

The distributors of the Mahima, Nya Bidroh and Prakashpunja weeklies were also the targets of intimidation.

Nepal is ranked 118th out of 179 countries in the 2013 Reporters Without Borders press freedom index.